Learning to Code before & during the AI Revolution - Part 1 - Before the Great Coding Madness

Before AI could generate software on demand, learning to code meant learning slowly, visibly, and often imperfectly. Constraints were everywhere: limited memory, slow processors, scarce documentation, and no safety net of tutorials or instant answers. This part looks at what it was like to encounter computing as a teenager in the 1980s, how early machines shaped curiosity, and why effort and understanding were inseparable. This is not nostalgia for its own sake, but context for how a generation learned to think in systems.

In “the old days”, things were very different. You had to learn a skill, practise it, and use it regularly. There were no shortcuts that produced convincing results without understanding. I remember that world, although it gets hazier every year.

The marketing message today tells us that anyone can code. The reality, as we will see across this series, is not black and white. To understand where we are now, it helps to start with what learning to code actually looked like at the start.

Warning: this will be nostalgic.

In the Beginning…

Many people contributed to the personal computer revolution of the late 1970s and early 1980s, but the one that stands out most clearly in my memory is Sir Clive Sinclair. Not for the deathtrap that was the C5, but for the ZX81 and the ZX Spectrum. I barely remember the ZX80, which is probably for the best.

Apologies to Jobs and Wozniak, who were likely the true geniuses here, but only one person in my entire school owned an Apple II, so they do not feature heavily in this story.

The ZX81 had 1K of memory. There was a 16K expansion pack which, when attached, usually crashed the whole thing. That was not a metaphor. It physically wobbled.

At the top end of our town was a small PC shop that we visited whenever we could, usually on Saturday mornings. It had a U-shaped bench running around the walls, and on it sat the personal computers of the day: VIC-20, ZX81, ZX Spectrum, BBC Model A and B, New Brain, Commodore PET, TI-99, Oric-1, Apple II (maybe), and the Lynx.

We drifted from machine to machine, typing commands, playing games if they were loaded, and generally pressing keys until we were either kicked out or felt we had overstayed our welcome.

I still remember a mate typing the SYS command on a Commodore and being completely transfixed by what it might do. Execute code at a specific memory address, apparently. Dangerous knowledge for young minds.

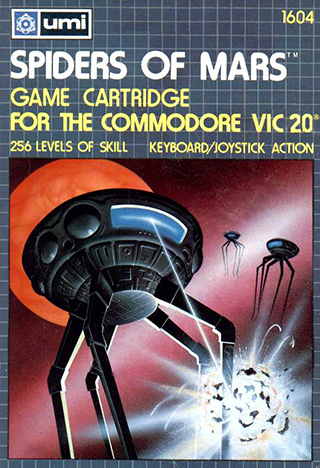

What really hooked me was seeing Spiders of Mars running on the VIC-20. It required a cartridge to expand memory just to display that many colours and pixels. It felt like magic.

Make it stand out

Spiders of Mars was a game for the VIC-20 in released in the early 80s. It came on a cartridge - a genius idea from Commodore which enabled the VIC to play games with far more memory, instant load and guarenteed “no crashes”, better graphics & sound and faster games due to memory mapped hardware and machine code accelerators.

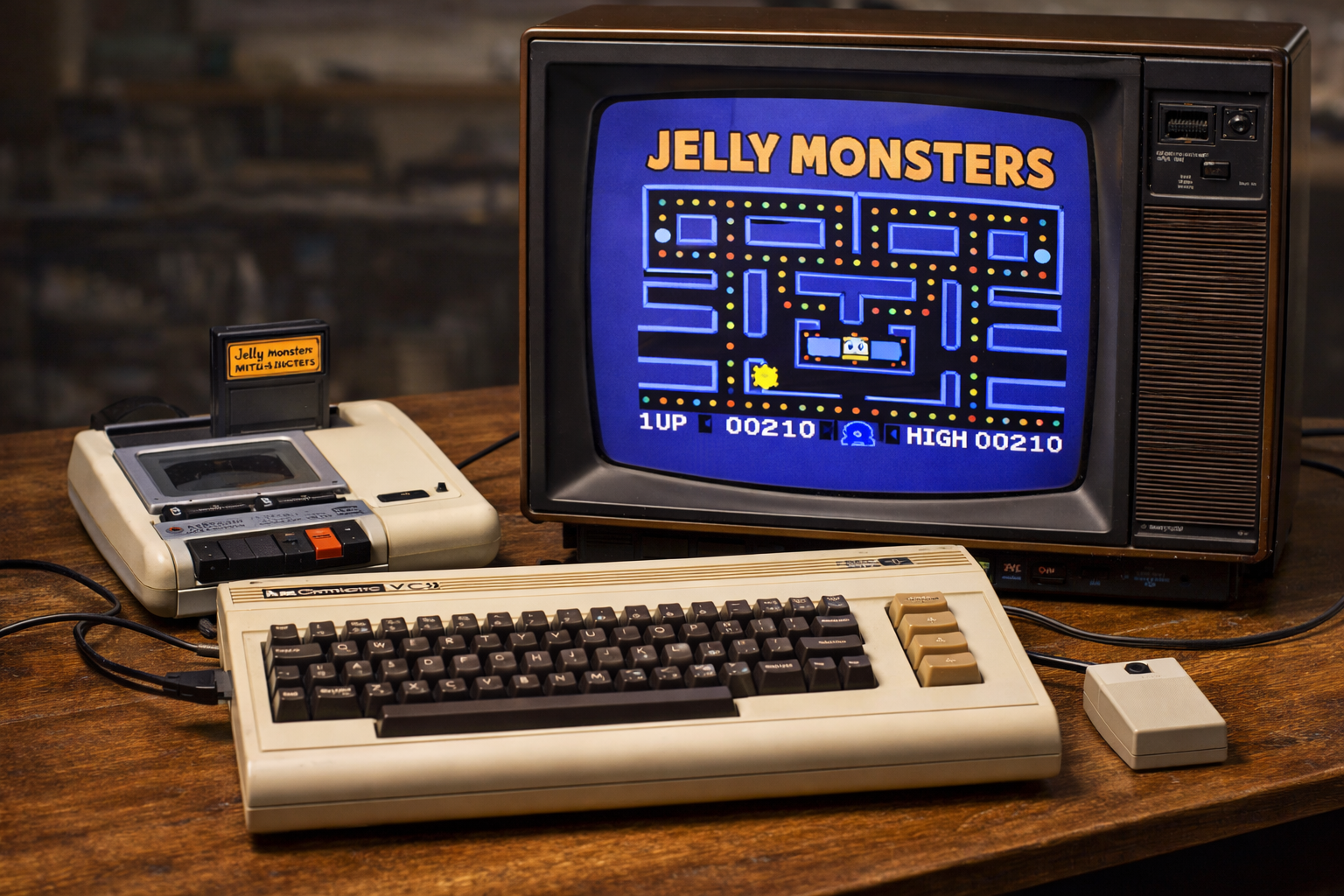

The “Jelly Monsters” game was so good that Commodore were sued by Atari

Memory: then vs now

Most modern computers have around 8GB of memory.

That is 8,589,934,592 bytes.

The VIC-20 I eventually owned had 3.5KB.

That is 3,584 bytes.

Today’s computers have roughly 2.4 million times more memory.

Every decision you made was constrained. Every line of code had some weight.

Learning to Code

Eventually, I persuaded my parents to buy me a VIC-20 for £200 (GBP). For that price you got:

3.5KB of memory

no hard drive, only cassette tapes

no mouse

a 1MHz processor

16 colours

a resolution of 176 × 184

basic audio and video

It came with BASIC, and that is what we learned.

Some people learned Assembly. The true nerds. BASIC was more than enough for me. I could program, experiment, and make simple games. I could see cause and effect immediately. That feedback loop was important to me.

Learning to code in the 1980s meant reading the manual and buying computer magazines like Your Computer. There was no YouTube, no Stack Overflow, no endless blogs explaining the same concept in twenty slightly different ways.

We had time and enthusiasm.

In my view, those two things are still the bulk of what you need in 2025. The difference now is not access to information, but filtering out the noise.

You learned by trying things. You broke them. You fixed them. Slowly, mental models formed. They stuck because they had been earned.

That is an important word. Earned and just to be clear - it is as important today to me and you as it was then.